You might assume that a study in psychology, regardless of where it was undertaken, can be applied to our understanding of human nature as a whole - that, for example, the attachments formed between mother and baby are universal and will be the identical regardless of where a person lives.

However, this assumption has been challenged by those studying cross-cultural psychology, a field of research which analyses cultural biases in the way other research is carried out, and the influence of our society on the way we think and behave. Researchers have discovered that subtle differences between cultures mean that the findings of an experiment in the U.S. cannot necessarily be applied to our understanding of human behavior in a different culture, such as Japan, for instance.

In this article, we look at the challenges facing psychologists in producing experiments that accurately understand behavior across different cultures, and some interesting findings of psychological studies into cross-cultural differences.

Defining Culture

To understand psychological differences amongst cultures, we must first define what we refer to as "culture" and how this can differ from simply the "place" in which we live. In psychology, culture refers to a set of ideas and beliefs which give people sense of shared history and can guide our behavior within society. Culture manifests itself in our language, art, daily routines, religion and sense of morality, among other forms, and is passed down from generation to generation.

Of course, within each culture we often see the influence of other cultures, such as that of other European languages on the English vocabulary, along with wide cultural variations within each country. So, whilst cultures and their boundaries remain fluid, in the study of cross-cultural psychology, research often focuses the differences in cultures at national levels (e.g. between the US and Japan).

Individualism vs Collectivism

One of the key distinctions between national cultures, which can influence the choices that people make, is that of individualistic versus collectivist societies:

-

Individualistic Societies

Individualistic societies focus on needs of the individual person and encourage each person to strive to achieve their own potential, often in competition with, or sometimes to the detriment of, a person's peers. It emphasises the importance of self-reliance and give each individual the freedom to be oneself, nurturing the idea of self expression.

Many countries in the West, such as the US, UK and other Western European countries are widely considered to be individualistic societies.

-

Collectivistic Societies

In contrast to individualistic societies, collectivistic societies emphasize the importance of cooperation - working for the benefit of the collective - and assume that societies can only improve by a group effort amongst all members of the community.

Collectivistic behavior may see altruistic acts or favors being carried out without the expectation of a reward other than that which benefits society. For example, a person may work extra hours without additional reward to fix a well, knowing that it will help to satisfy their fellow villagers' need for water.

Collectivism is generally found in Eastern cultures - in countries such as Japan - and also in smaller groups such as Kibbutz farming communities in Israel, where each member works towards the town's collective goals.

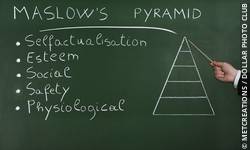

The field of psychology has long been dominated by Western schools of thought which have focused on individualistic-oriented approaches to explaining behavior. For example, the Swiss psychoanalyst Carl Jung distinguishing the individual from the wider his or her wider setting, writing about the concept of the Self and the internal conflicts that affect their thoughts. Sigmund Freud, attributed behavior and our anxieties to inner, unresolved conflicts between the id, the ego and superego, whilst more recently, Abraham Maslow described human motivation as being driven by a set of internal desires in a Hierarchy of Needs.1

Yet, many of these theories ignore the wider, environmental factors which affect an individual's behavior, one of which is the influence of the cultural experiences that a person lives through and which must also affect the behavior of people who interact with them. Is there a reason for culture being looked over in the mission to understand our thoughts and behavior?

Bias in Experiments

The development of psychology as a discipline in the West has inevitably lead to many studies and experiments being carried out in individualistic societies and often more specifically, at universities. Moreover, in 2010, Canadian psychologist Joseph Henrich and his colleagues identified that the participants of such studies tended to be W.E.I.R.D. - Western and Educated, and from Industrialised, Rich and Democratic countries (Henrich et al, 2010).2 This leads to the question of whether the findings of key psychological studies carry external validity outside not only the experimental situation, but whether they can be generalized to apply outside of the society and culture in which the studies were carried out.

Such criticism of psychology studies from a cross-cultural perspective has lead to researchers attempting to replicate experiments' findings in countries other than their original location. Yet this presents a second problem - is there an inherent cultural bias in the experimental methods used to observe behavior? For example, people in the U.S. have been found to interpret emotions using different facial features to those in other China, for example (Jack, 2012).3 This casts doubt on whether the same techniques can be reliably used to observe and record emotions in a US study as in an experiment carried out in another culture.

Cultural Differences in Relationships and Attachments

One groundbreaking area of research in psychology was that of interpersonal relationships, and the impact that social interactions as an infant have on a person later in life. Mary Ainsworth developed the Strange Situation test (Ainsworth and Bell, 1970) which built on the work of John Bowlby to demonstrate the different types of attachment to the caregiver that infants experience, including secure, anxious-resistant and anxious-avoidant attachments.4 Such attachments have been widely recognised and are still used in understanding parent-child relationships today. However, in the Strange Situation test, Ainsworth's subjects were from middle class, Caucasian backgrounds - a demographic which struggles to represent the cultural makeup of the US, still less other countries.

Following numerous studies attempting to replicate Ainsworth's Strange Situation test in non-US cultures, a meta-analysis of the studies revealed that across individualistic and collectivistic cultures, secure attachments were the most common bond formed between parent and child (Ijendoorn and Kroonenburg, 1988), as in the US study.5 However, in the Western countries studied, the remaining attachments formed were primarily insecure-avoidant - infants showed limited anxiety when the caregiver left them, were relatively unphased by a stranger entering the room and took little comfort from the caregiver returning. By contrast, in Eastern cultures, the remaining attachments were mainly resistant avoidant - the infants became anxious when the caregiver left the room and in the presence of the stranger.

In another study, researchers in Detroit carried out a meta-analysis of studies into the effect that having children can have on couple's relationships. Dillon and Beechler (2010) found that in both individualistic and collectivistic cultures, relationships were reported to be impacted to some degree. However, the negative effect was more significant in individualistic societies. The researchers attributed this difference to the way in which the responsibility for childcare is often shared among different caregivers in Eastern societies, whereas in the West, the mother-child bond may be much stronger as infants tend to be cared for primarily by their mother.6

Cultural differences in emotions

Relationships are not the only focus of study which have been observed to differ among cultures. As we have seen, the participants of studies in the US and China have been seen to use 'tells' - information gathered from facial expressions - differently when judging a person's emotional state.2

Cultural differences with respect to emotional intelligence have also been identified in participants in a Japanese study, in which participants were shown cartoons of people displaying varying emotions, surrounded by people who either showed the same or a different emotion.

The researchers found that Japanese participants were more likely to evaluate the emotions of those surrounding the central person when trying to judge their emotion than Western participants did (Masuda et al, 2008).7 This indicates the influence of a collectivist culture in taking into account the emotions of the whole group, rather than focussing on an individual's emotional state.

Culture and measuring intelligence

Cross-cultural analyses of psychology studies has also had implications for the way levels of intelligence are measured among populations. We might believe that intelligence can be measured objectively, and in the West, the Intelligence Quotient (IQ) test is commonly used to quantify and compare people's intelligence. However, across different cultures, this does not always provide an accurate measurement. One study by Sernberg and Grigorenko (2004), which took the view of intelligence as being a practical ability to survive, measured Kenyans' ability to identify the correct type of herbal medicine to use for infections - an essential skill in their environment. Researchers compared the participants' ability to their intelligence as measured by tests used to quantify intelligence by Western standards, including those evaluating vocabulary and cognitive skills.

The results of the two types of test - one culturally specific and one Western-orientated - had minimal correlation, showing that intelligence in one culture is not necessarily useful in another.8

Designing better studies

Studies revealing cross cultural differences in such areas have lead to better methodology and more acute criticism of psychological research with regards to its generalisability. John Berry (1969) distinguished between two approaches to research. Firstly he identified emic studies, which focus on a specific culture and do not necessarily carry external validity outside of that culture. The second approach is etic - research which recognises the inherent cultural biases of an experiment's methodology and attempts to either use techniques which can be applied universally, or to use researchers who are familiar with a culture and can create experiments with methods that are suitable for that culture.9